A Gentle Introduction to CRDTs

Conflict Free Replicated Data types (CRDTs) can be tricky. You may spend months reading papers and implementing different algorithms before they finally click and become simple. That or they'll seem simple out of the gate and you'll be missing a bunch of nuance.

What follows is an attempt at distilling all the hard understanding work into a condensed and easy to understand set of reading for a software developer without any background in CRDTs or distributed systems.

Outline of what's to come:

- The quick definition of a CRDT

- When you need a CRDT

- More About What a CRDT is

- A Simple CRDT

- Last Write Wins & What Can Go Wrong

- Getting More Complicated and Rethinking Time

Quick Definition

From Wikipedia:

A CRDT is a data structure that is replicated across multiple computers in a network, with the following features:

- The application can update any replica independently, concurrently and without coordinating with other replicas.

- An algorithm (itself part of the data type) automatically resolves any inconsistencies that might occur.

- Although replicas may have different state at any particular point in time, they are guaranteed to eventually converge.

We'll clarify and expand on this definition later.

When you need a CRDT

CRDTs are needed in situations where you want multiple processes to modify the same state without coordinating their writes to that state.

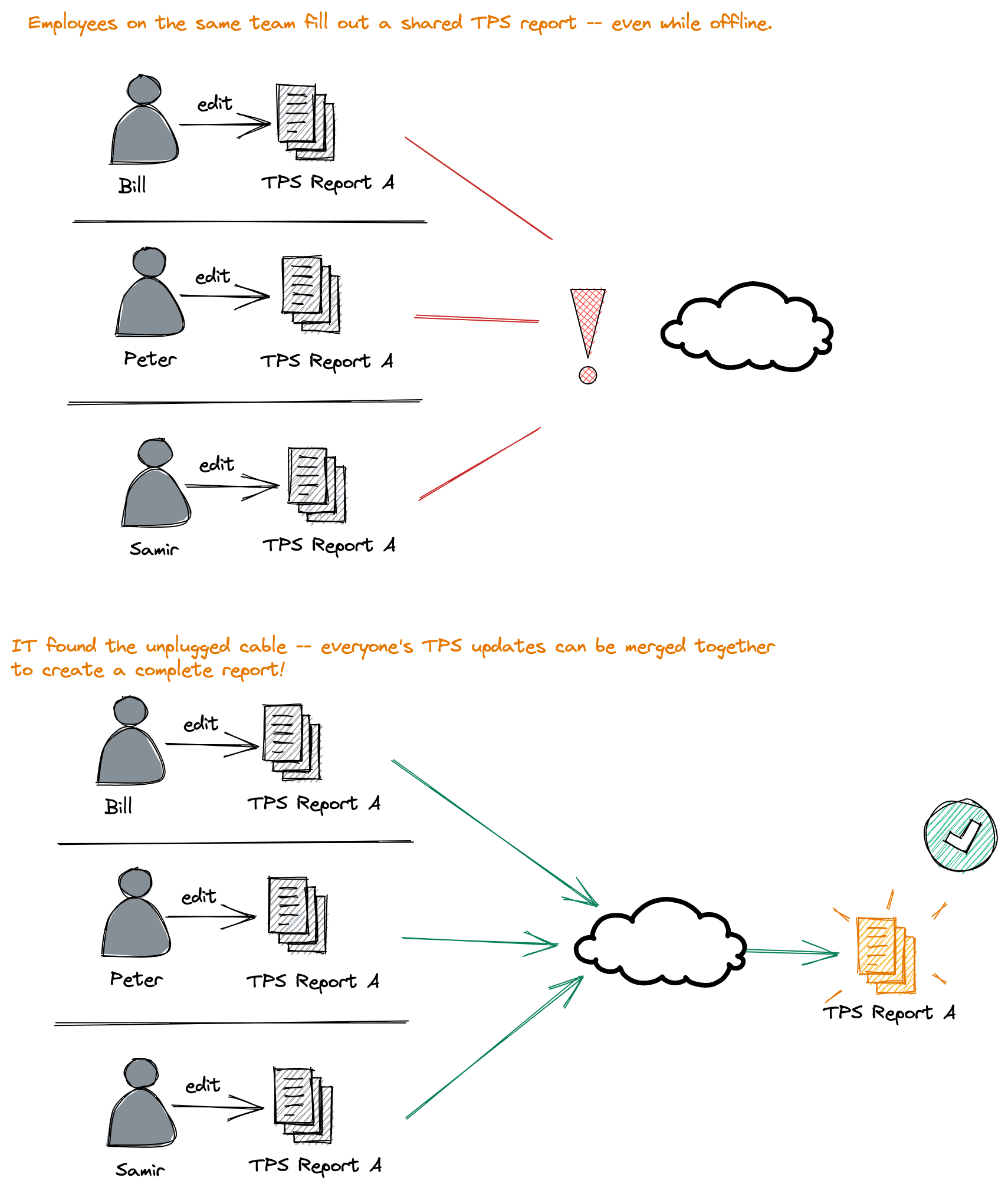

Imagine a situation where you have a shared business document. Ideally you, and others, can modify your copies of that document even when internet access is down. When internet is restored, you and your peer's changes can all be merged together without conflict.

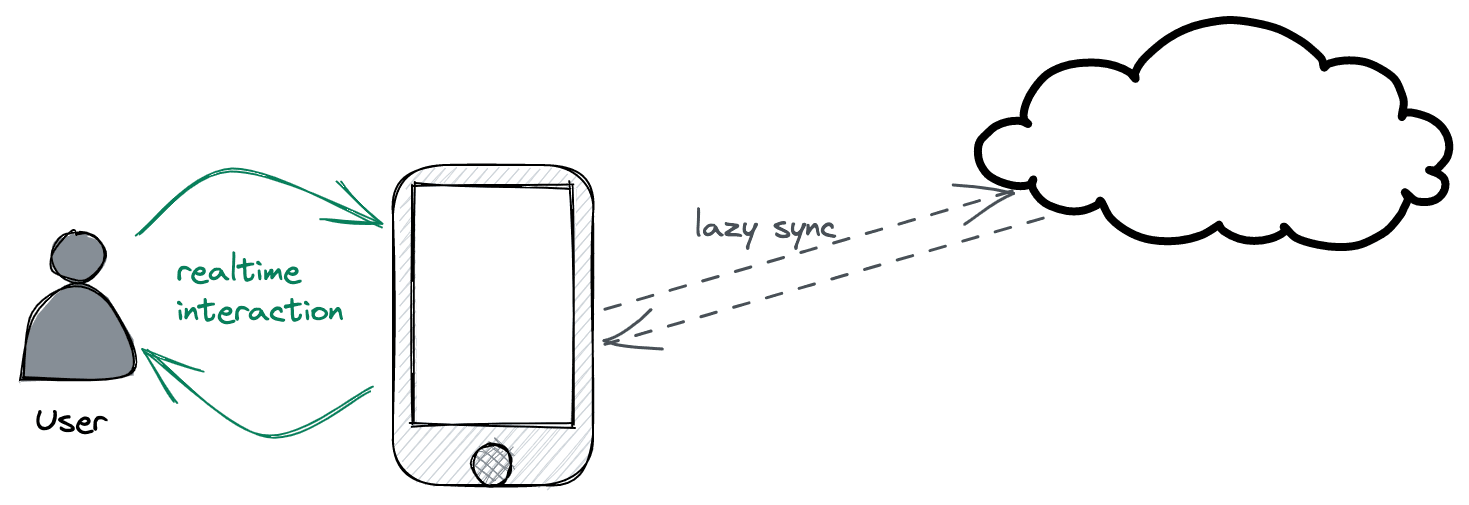

Even in situations where you do have excellent connectivity, CRDTs are useful to present a realtime experience to users. CRDTs allow all writes to be processed locally and merged with remote nodes later rather than requiring round-trips to a server for every write.

Lastly, CRDTs can be merged in any order so changes don't need to go through a central server. This allows truly "serverless" setups where every node is a peer on equal footing, able to merge state with any other peer at any time.

What I'm describing here is very similar to decentralized version control (e.g., git and mercurial). In git, you commit locally and eventually merge and push your changes into a remote repository. Unlike git, CRDTs don't have merge conflicts. Conflict resolution is handled by the CRDT algorithm itself. Although not exactly a CRDT, git will be a useful model to refer back to since it is something already familiar to most developers and incorporates similar concepts.

We're not yet ready to tackle the complexities of git so let's start with understanding what a CRDT is and then looking at one of the simplest crdts.

What is a CRDT?

I'll skip the mathematical definition (lattice, join, meet, etc.) for now and focus on a practical definition.

A CRDT is a data type that can be:

- Copied to multiple machines

- Be modified independently by those machines without any coordination and for any length of time

- All divergent copies of that state can be merged back together in any order and by any machine. Once all machines have seen all divergent copies, they're guaranteed to have all converged to the same final state.

The last point is important given it allows peer to peer merging of state rather than requiring merges to go through a central server. We'll come back to this to understand why algorithms which rely on merging state in a cetnralized way can't always be applied in a peer to peer setting.

Going back to git, it's the same as giving every developer a copy of the repository and allowing each developer to make changes locally. At the end of the day, every developer in an organization can merge changes with every other developer however they like: pair-wise, round-robin, or through a central repository. Once all merges are complete, every developer will have the same state (assuming merge conflicts were deterministically resolved). Unlike git, a CRDT wouldn't hit merge conflicts and can merge out of order changes.

Let's see how this actually works and how you can implement it in the large (full blown applications) and in the small (individiual fields in a record).

A Simple CRDT

One of the simplest CRDTs is a set that can only grow. A set being defined as:

- An unordered collection of elements

- Each element in the collection is distinct

- Adding an element to a set that is already in the set does not change the set

So your normal Set type in Java/JavaScript/Python/etc.

A set that only grows is a CRDT since:

- You can give a copy of that set to any number of nodes

- Each node can add any elements it likes to its copy of the set

- All sets from all nodes can be merged back together in any order

- Once all merges are complete, all nodes will have the same set (the union of all individual sets)

A slightly more useful incarnation of a grow only set is a database table where each row is keyed by a UUID (tangent: use uuidv7 for primary keys (opens in a new tab)) and only inserts are allowed (no updates or deletes).

A table structured in this way can always be written to by separate nodes and merged back together without conflict since it is a grow only set. Use the example below to add rows to different grow-only tables and then merge them together.

| id | content |

|---|

| id | content |

|---|

Merge Result

| id | content |

|---|

A grow only table is intereseting but you'll eventually want to do one or more of the following:

- Modify a row

- Run a reduce job over a set of rows to come up with a "view" of some object state

- Delete a row

So how can we support all of this in a conflict-free way? Let's look at row modifications first.

The simplest trick for merging rows is to "take the last write." Two people wrote the same row? Take whomever's write is newer. This approach is pretty straightforward but, aside from losing writes, there are ways it can go wrong that are not always apparent.

Looking into the ways it can be incorrectly implemented will help us understand why CRDTs have the properties they do and how to build a correct one.

Last Write - What Can Go Wrong?

We'll take that "last write wins" is acceptable for the use case as a given. Now let's take some stabs at implementing a grow only table that supports last write replacements of rows.

The first solution would be to timestamp rows with the current system time of the node that did the write. Remember we need nodes to be able to work without internet connectivitiy so we only have access to that node's local clock.

From simplest to most complex, the four common mistakes in a last write wins setup are:

- Forgetting to update the loser's timestamp

- Having the wrong tie breaker for concurrent edits

- "Clock Pushing" when one node proxies another

- Trusting system time!

Error 1: Forgetting to Update the Loser's Timestamp

When a node merges with another node and they both changed the same row, we'll take the row with the highest clock value. This can go wrong if we forget to update the timestamp of the row along with all the other values in that row. I.e., if we don't fully replace the losing node's row with the winning node's row.

Node A:

| id | content | time |

|---|---|---|

| x | this | 13:01:01 |

Node B:

| id | content | time |

|---|---|---|

| x | that | 12:00:00 |

A<->B merge and say B does not update the time for it's row to match the max between A's row time and B's row time.

Node B, after incorrect merge:

| id | content | time |

|---|---|---|

| x | this | 12:00:00 |

Now if Node C comes along with a modificaiton to the same row, but at time 12:30, it'll overwrite the current value. This, however, isn't the last write since A's write was later. We now have an inconsistent state.

This is a trivial bug but covering it will help to understand logical clocks. To reiterate, the correct solution is to take the whole row including timestamp.

Error 2: Forgetting & Inconsistent Tie Breaking

This error is about not having a correct tie breaker for concurrent edits. It is possible that two processes provide the exact same time for an update. If you do not handle this case in a specific way you will end up with divergent state between processes.

Maybe concurrent edits are unlikely in your case but:

- You should never rule them out and

- We need to cover it since the 4th error, and solving the 4th error, will make this one more likely.

| id | content | time |

|---|---|---|

| x | z | 12:00:00 |

| id | content | time |

|---|---|---|

| x | b | 12:00:00 |

| id | content | time |

|---|---|---|

| x | a | 12:00:00 |

The two common ways of getting the tie breaker wrong when there are concurrent edits are:

- Forgetting about tie breaking entirely

- Always taking a peer's value on concurrent edit

I.e.,

Forgetting (Always Rejecting)

// we forgot the `peer_time == my_time` case!

// We are always rejecting the peer_value on concurrent writes.

if (peer_time > my_time) {

my_value = peer_value;

}and

Always Taking

// Better but also unsafe. Always taking the peer_value on concurrent writes.

if (peer_time >= my_time) {

my_value = peer_value;

}To solve this there are two options:

- Choose the greatest value when there are concurrent edits

- Choose the value from the node with the largest node name

Going with option (1), all nodes will choose z as the winner (z > b > a).

Going with option (2), all nodes will choose a as the winner (node name C > node name B > node name A).

You can test each strategy by trying out the example above -

- Choose a tie breaker

- Merge every node's state into every other node's

- No matter what order you merge things, the end result will be convergence except in the always reject and always take cases. Always reject will never converge. Always take will converge or not converge depending on the order in which peers merge.

Always take is somewhat subtle. To make it fail to converge in the example:

- Merge C into A

- Merge B into A

- Merge A into B

- Merge C into B

- Your last two choices don't matter. You're already inconsistent.

Error 3: Clock Pushing when Proxying Changes

This isn't strictly related to last write wins but will come up when you want to start syncing partial updates from a source to a destination. As in, sync all changes that haven't already been synced.

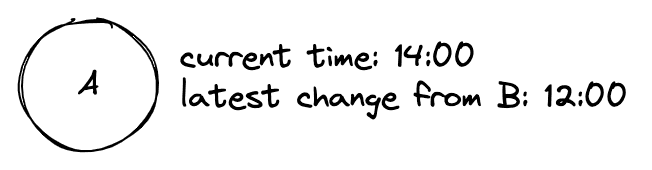

To do this, you'll need a way to figure out all changes a node has that you do not have. The simple way is to record the max timestamp from a node that you have merged with. Next time you merge, you ask for all rows after that timestamp.

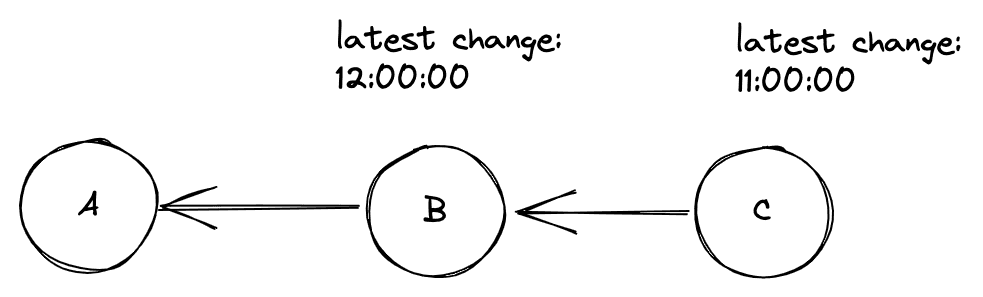

This, however, can break when nodes acts as proxies for other nodes in the network.

Imagine this case:

- Node A has all changes from node B up and until

12:00:00, - Node B receives changes from node C which includes rows created prior to

12:00:00since B hasn't synced with C in some time. - Node A now wants all changes from B again but asks for changes after

12:00:00since it thinks it already has all changes up to that time.

If A will eventually talk to C on its own, this may not be a problem. If B is going to proxy changes from C and forward them to A, this will be a problem. A will not ask for the old rows B received from C since A believes it is up to date with B up to 12:00:00.

So what can we do?

An incorrect solution is to "clock push" -- to record the timestamp for the row as being max(current_time, row_time). This makes old writes look new and starts breaking merges down the line.

A correct solution is to retain two timestamps for a row:

- The time the row was written (created or updated) by whomever wrote it. We'll call this

row_time - The local time of the process upon reception of or local modification of the row. We'll call this

local_row_time

The latter timestamp can be used to track changes_since and is always set to current time whenever a row is inserted or updated on a node -- either via local update or sync. The former timestamp is used for merging.

| id | content | row_time | local_row_time |

|---|---|---|---|

| x | foo | 13:00:00 | 14:00:00 |

| y | bar | 12:00:00 | 14:30:00 |

| z | baz | 13:04:01 | 13:20:32 |

In our proxy example:

- When B receives new rows from C, it tags all those rows'

local_row_timecolumn with current time. - When A wants changes from B, it tracks

changes_sinceby recording the largestlocal_row_timeit has seen from B - Merging is done via

row_timeso last write semantics are still corretly respected.

You can play with the idea below. Note that each node's local time is just a simple integer counter in this case. Works just as well as (actually better than) system time for our purposes and is a gentle introduction to the next error.

| id | content | row_time | local_row_time |

|---|

| id | content | row_time | local_row_time |

|---|

| id | content | row_time | local_row_time |

|---|

Error 4: Trusting System Time

You can't trust system time. Even more so in a distributed setting. Multiply that distrust in a distributed setting where internet is spotty. Forget about it in any setting where you do not control the devices.

System time moves with its own rules and breaks many assumptions we have about it.

- An error of just .001% in your system clock results in 1 second drift per day (opens in a new tab). If your clock is not often re-syncing its time, it will get off. Re-syncing can also cause your clock to move backwards if it was ahead.

- Users can change their system time resulting in meaningless values and later events getting timestamped before earlier ones

- Introduction of leap seconds (opens in a new tab) which can cause time to run backwards within a single process (opens in a new tab).

- Different cores on a machine can have different values for the current system time (opens in a new tab).

About Time

So how do we handle time? CRDTs do not require a notion of time -- it isn't part of the strict mathematical definiton. Mike Toomim (opens in a new tab) has a great quote about how CRDTs collapse time, they remove time from the equation.

Take a grow only set as an example. Time doesn't matter -- the state can always merge and merge at any point even without knowing about time.

Even so, "time" is going to be an important factor in many CRDTs since -

- Users will want to know what happened before what

- For something like last write wins, we want to know which writes happened before which

- Time helps figure out deltas between state for efficient syncing

Given we shouldn't trust system time and can't trust it where we're going (distributed, possibly peer to peer, and unknown connectivity) we need to free our mind from the common conception of time.

What we really care about is what events could have caused what other events. If two devices never communicate then what transpired on one could not have caused events to transpire on the other (ignoring backchannels). If the devices do communicate then you have a watermark at which to divide what events could have caused (and thus happened before) what other events.

Concretely, if I create a new document on my device but never send it to you then clearly you can't have made edits to that document. We don't need the system clock to tell us that. We can generalize this to everything about participants and events in a network in order to get a stable logical clock that allows us to partially order all events in the system.

That is probably about as clear as mud so let's build a logical clock to understand this a bit better.

Basic Logical Clock

The simplest logical clock implementation is simply to keep an integer in your process that you increment for every event. Each event gets timestamped with this counter.

Because I've had engineers worry about this in the past: a 64bit unsigned integer can be incremented 1 million times a second for 6,000 centuries before overflowing.

2^64 / (10^6 * 60 * 60 * 24 * 365 * 100) ~= 5,8490 (I'll wait...)

To totally order events within your process, order by that timestamp. To scale this up to many cores, use an atomic integer that you can compare-and-swap (opens in a new tab).

But how can we keep time across many devices? And without coordinating? Or if we're perf sensitive and don't want any contention between cores via a shared atomic int?

Logical Clocks, Distributed

A distributed logical clock builds upon the basic logical clock. Every node keeps their own independent counter that they increment on their own. The one key change is that whenever two nodes exchange information they also exchange clock values. Each node then sets their internal clock to max(peer_clock, my_clock) + 1.

This change lays the foundation for being able to determine what happened before what across many loosely connected peers in a network.

Happens-before, Explained

This solves the issue of not having a clock in our control. We control the counter since it is internal to whatever software we're deploying. We also know the counter will never run backwards. A surprising thing we now know is that if an event we receive from a peer has a greater clock value than our clock, it must have been a concurrent or later write. It could not be a write that happened before our writes.

That last sentence is probably a head scratcher. Surely a lower logical time on node A could have happened after a larger logical time on node B. In terms of wall time this is true. In terms of causality, it is not. A lower time event on node A could not have been caused by a higher time event on node B. For that to have happened, node A's clock would have to be greater than node B's given we bump local logical clocks forward when nodes communicate.

Alas, clocks deserve their own separate discussion. There are limitations with the described clock and there are better logical clocks with more guarantees to consider and compare against.

Suffice it to say: time, when considered as "what caused what", is best thought of as a DAG (opens in a new tab).

We'll explore this in-depth and implement "event sourced CRDTs" and sequence/text CRDTs atop it. We'll also dive deeper into supporting deletes, sorting, counters, updates of individual columns in a row and more.

Eventually we'll get into the theory and abstract definition of a CRDT.

Wrapping Up

If you just want CRDTs in your relational database then try vlcn and cr-sqlite (opens in a new tab)! We're solving all of these problems and bringing a simple, declarative and easy to use APIs to CRDTs!

CREATE TABLE foo (id primary key NOT NULL, bar, baz);

SELECT crsql_as_crr('foo'); -- (crr means conflict free replicated relation)We're even thinking about things like foreign key constraints, transactions, garbage collection and more!