A Framework for Convergence

What if I told you anyone can create a new CRDT (opens in a new tab)? That with no special knowledge, you can write a set of mutations that can be applied to a data structure in a way that is guaranteed to converge? That you can do this without any locks, mutexes, coordination, or other concurrency primitives? That you can do this without any special knowledge of distributed systems?

Nobody can be told this truth. They must see it for themselves.

Diving In

We'll start with an initial state --

And then let you author any mutation you want to update that state. The only rules are:

- Your mutations must be deterministic..

- If the mutation is a no-op it should return false.

- The first argument to the mutation is always

state - Additional arguments for the mutation come after

state

Some example mutations have been provided for you.

After making any changes to the code, press shift + enter or the play button (top right of the box) to re-run the code and update the example.

Let's see this in action.

Below are three independent UIs, representing nodes or processes, that are driven by three independent copies of state. On each one you can run your mutations, updating the state for that specific node. Whenever you desire, have the nodes merge their state together by pressing the "sync nodes!" button.

Pretty cool, right? All of the nodes converge to the same state on merge and you didn't have to write any special code to make this happen or use any special data structures. You just vanilla JavaScript and the framework took care of the rest.

Before we get into how this works, let's talk about intent. While CRDTs and other structures may meet the mathematical definition of convergence it is likely that they will not meet the user's expectations of convergence.

Depending on what examples you ended up writing for yourself, you may have already noticed the intent problem.

Intent

How do we preserve the user's intent and how does the mathematical definition of convergence deviate from practical expectations?

To understand this better, we'll look at a delete operation that is based on array index.

deleteItem(state, index) {

if (index < 0 || index >= state.items.length) {

return false;

}

state.items.splice(index, 1);

}This mutation is deterministic and it will converge but it doesn't preserve intent.

A few ways it can fail to preserve intent:

- Two users trying to delete the same item concurrently will result in two items being removed

- Trying to remove an element, by array index, could end up removing a completely unrelated element after merging states.

The above cases are illustrated below.

Fig 1: Both users attempt to delete the letter

bconcurrently. Since the mutation uses array indices,bandcare both removed on merge rather than justb.

Fig 2: Both users concurrently create a list of items. User 1 then removes

cfrom their list (index 2). Post merge,bends up being removed!

The problem with both examples is that we're using array index (or alias) to indirectly reference what we are actually talking about.

Fixing Intent

While yes, you can create a CRDT without any special knowledge you can't create a CRDT that preserves user intent without some knowledge.

Many types of intent (delete, move to, insert at) can be preserved by knowing a few principles and following them when writing mutations.

Intent Preserving Principles

Refer to items by their identity

When you're operating on something, you need to refer to that thing exactly rather than using an indirect reference.

This is most clearly illustrated in the mutations that used array indices to talk about what to remove. If, instead, each element had a unique ID and we passed that to mutations when deleting / moving / etc., the user's intent would be preserved.

Example

addItem(state, id, item) {

if (state.items.find((i) => i.id === id)) {

return false;

}

state.items.push({

id,

item,

});

},

deleteItem(state, id) {

const index = state.items.findIndex((e) => e.id === id);

if (index == -1) {

return false;

}

state.items.splice(index, 1);

}Fig 3: The updated mutations. Note that the item id must be passed in to the mutation. Generating a random uuid within the mutation would make the mutation non-deterministic.

Go ahead and try those mutations yourself or watch the example --

Fig 4: Both users concurrently remove

A_2or itemb. After merging, that is still what both users see in contrast to the array index based removal.

Position is Relative

If you need to prevent interleaving of sequences, use relative positions.

This is similar to the array index idea. Our addItem mutation is implicitly using array index as the sort order for items. This is fine for many use cases but for other use cases, such as text insertion, this is problem. The reason is that concurrent edits in the same location will end up interleaving characters.

E.g., if Node A writes "girl" and Node B concurrently writes "boy" the result post-merge will be "gbioryl".

We can fix this by making the notion of position relative. That is, the position an item was inserted at is identified by what is to the left or right of that item.

addItem(state, id, rightOf, item) {

if (state.items.find((i) => i.id === id)) {

return false;

}

let index = state.items.findIndex((e) => e.id === rightOf);

if (index < 0) {

index = state.items.length;

}

state.items.splice(index + 1, 0, {

id,

item

});

}Give it a whirl in the live example or see the video below --

Fig 5: using "right of" to relatively position new insertions. No interleaving!

There could still be a problem here, however. What if another user concurrently deleted something you were inserting next to?

Relative positioning would break down in this case. If you want to insert next to b1 but b1 no longer exists after a merge then your position no longer exists.

You could fix this with invariants (do not allow deletion of these sorts of things) or soft deletion & tombstoning. Tombstoning an item would drop its content but retain its id and position so position information always exists. In addition to the problems outlined for sequences, we can run into issues when moving structures around that have pointers to one another. E.g., moving folders inside a file tree. Concurrent edits of this tree can create cycles such as a folder that contains itself.

While this framework idea is powerful (we got relatively far with 0 knowledge of CRDTs) certain cases can begin to explode in complexity.

Other Options for Intent

A different approach to preserving intent is to reach for an existing CRDT (opens in a new tab) that has the intention preserving properties you'd like. This where we're headed with Vulcan. The end goal being a declarative extension to the SQL Schema Definition Language to allow you to easily combine the behavior you need:

CREATE TABLE post (

id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY NOT NULL,

views COUNTER,

content PERITEXT,

owner_id LWW INTEGER

) AS CausalLengthSet;Fig 6: The north star syntax of cr-sqlite.

At some point we might ship a "convergence framework" idea to provide a simple way to author custom convergent data types when those that are available don't meet your needs.

If any of this sounds interesting to you, schedule some time with me (opens in a new tab) to discuss it or:

- CRDTs

- Contributing to cr-sqlite

- Integration into your product, sponsorship, investment, contract work, design partnerships, etc.

Even though there are drawbacks the framework seems pretty magical. For many cases you can just write normal business logic and the state you mutated will converge as expected. How does this work?

Framework Implementation

The framework is split into two parts:

- A log of mutations

- Machinery to merge and apply the log to the application's state

Mutation Log

Every time one of the named mutations is run, we log it. The log looks like:

type MutationLog = [EventID, ParentIDs[], MutationName, Args[]][];In a system that isn't distributed the log would be linear. In our case, however, we need to account for concurrent edits happening in other processes. This is where ParentIDs comes in. ParentIDs refers to all the mutations that happened immediately before the current mutation.

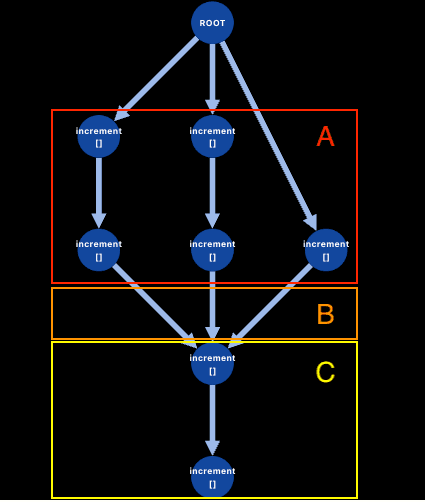

Thus the log, rather than being linear, is a DAG. The relationships in the DAG express time.

- Branches represent concurrent modifications.

- Branches that converge into a node represent events that happened before the node being converged into.

- Linear runs represents events that happen one after the other

- Linear runs in separate branches are concurrent sequences of events.

Fig 7: 3 processes incrementing a distributed counter.

- (A) Two processes increment the counter twice (concurrent sequences of events) at the same time a third process increments it once (concurrent event).

- (B) All processes sync their changes (arrows converging)

- (C) A single process increments the counter twice more after all concurrent events.

In this setup, each process can locally write to its log without coordinating with others. All it needs to do when writing is create a new event whose parents are the leaves of it's current copy of the log. In our interactive example, each mutation you define is decorated such that it calls addEvent when being invoked.

export type Event = {

mutationName: string;

mutationArgs: any[];

};

class DAG {

root: DAGNode;

nodeRelation: Map<NodeID, DAGNode> = new Map();

seq: number = 0;

...

addEvent(event: Event) {

const node: DAGNode = {

parents: this.findLeaves(),

id: `${this.nodeName}-${this.seq++}`,

event,

};

this.nodeRelation.set(node.id, node);

return node;

}

findLeaves(): Set<NodeID> {

const leaves = new Set<NodeID>([...this.nodeRelation.keys()]);

for (const n of this.nodeRelation.values()) {

// if p is a parent then it is not a leaf. Remove it from the leaves set.

for (const p of n.parents) {

leaves.delete(p);

}

}

return leaves;

}

}Syncing state between processes is a matter of merging these logs together and merging these DAGs is trivial. Since each node in the DAG is completely unique and immutable, all we have to do is union the sets of nodes. This unioning can happen in any order and is idempotent meaning convergence does not rely on the order the DAGs are merged and duplicate syncs are not a problem.

class DAG {

...

merge(other: DAG): DAG {

const ret = new DAG(this.nodeName);

ret.nodeRelation = new Map([...this.nodeRelation, ...other.nodeRelation]);

ret.seq = Math.max(this.seq, other.seq) + 1;

return ret;

}

}Since all processes share a common ancestor for their DAG (the sentinel "ROOT" element), the DAG will always be connected (opens in a new tab) after a merge. This ensures no events are ever lost by being orphaned.

Based on this, the DAG:

- Only grows

- Can be merged in any order (it is commutative and associative)

- Merges are idempotent

Meaning the DAG is a CRDT. Since we know that DAG will always converge across all peers we can use it to order and drive mutations against application state.

Which brings us to the last trick -- updating the current application state based on the DAG.

Updating State

Updating application state after a merge is a matter of:

- rewinding to a certain snapshot of application state (or all the way back to initial state)

- Replaying the mutation log against that state

But how do you replay a log that is not linear? You make it linear. Each process does a deterministic breadth first traversal (opens in a new tab) of the DAG to create a single sequence of events. This interpretation of events is what is applied to the state snapshot.

The area where this gets tricky is when handling concurrent branches. Since there is no ordering between concurrent events we just have to pick one and stick with it. A common way to order concurrent events is to order them by process id or value.

A non-optimized version of this based on our DAG structure:

export type NodeID = "ROOT" | `${NodeName}-${number}`;

export type DAGNode = {

parents: Set<NodeID>;

id: NodeID;

event: Event;

};

class DAG {

...

getEventsInOrder(): DAGNode[] {

const graph = new Map<NodeID, DAGNode[]>();

for (const n of this.nodeRelation.keys()) {

graph.set(n, []);

}

// Convert the graph so we have child pointers.

for (const n of this.nodeRelation.values()) {

for (const p of n.parents) {

graph.get(p)!.push(n);

}

}

// Now sort the children of each node by their id. IDs never collide given node name is encoded into the id.

for (const children of graph.values()) {

children.sort((a, b) => {

const [aNode, aRawSeq] = a.id.split("-");

const [bNode, bRawSeq] = b.id.split("-");

const aSeq = parseInt(aRawSeq);

const bSeq = parseInt(bRawSeq);

if (aSeq === bSeq) {

return aNode < bNode ? -1 : 1;

}

return aSeq - bSeq;

});

}

const events: DAGNode[] = [];

// Finally do our breadth first traversal.

const visited = new Set<DAGNode>();

const toVisit = [this.root];

for (const n of toVisit) {

if (visited.has(n)) {

continue;

}

visited.add(n);

if (n.id !== "ROOT") {

events.push(n);

}

for (const child of graph.get(n.id)!) {

toVisit.push(child);

}

}

return events;

}

}While toy versions of all ideas seem to be able to be implemented in 100 lines of JavaScript (opens in a new tab), a production grade version that:

- Scales to hundreds or thousands of transactions per second (no matter how large the transaction logs become)

- Shares structure and compresses well

will take some doing. Although you could certainly scale the toy to specific use cases with some hacks. For the general case you'll need:

- A data structure that can rewind to arbitrary versions easily (opens in a new tab)

- A way to calculate the deltas between DAGs on different nodes so as not to require sending the entire dag on sync

- Something to prevent mistakes such as mutations being non-deterministic

- A way to compress the log while still supporting random access to it

- A way to know when it is safe to prune events out of the log

Acknowledgements

- Replicache (opens in a new tab) and @aboodman (opens in a new tab) for turning me on to the idea with his presentation @ lfw.dev which you can view here (opens in a new tab)

- lfw.dev (opens in a new tab) and @founderYonz (opens in a new tab) for gathering a community together to share these ideas

- Braid.org (opens in a new tab) for being open, welcoming and truly diving deep on CRDTs, exploring them in every possible way